The Categorical Imperative: Split Up but Still Sleeping Together — Why Science, Philosophy and the Weird Stuff Keep Crashing the Same Party

# Split Up but Still Sleeping Together: Why Science, Philosophy and the Weird Stuff Keep Crashing the Same Party

# Split Up but Still Sleeping Together: Why Science, Philosophy and the Weird Stuff Keep Crashing the Same Party

You were told in college that science and philosophy grew apart: one got a lab, the other stuck to the coffee shop arguing about ethics. Cute story. Mostly bureaucratic, frankly. Underneath the velvet ropes they keep swapping notes—metaphysics lays the table, epistemology brings the platters, and ethics decides who’s buying the wine.

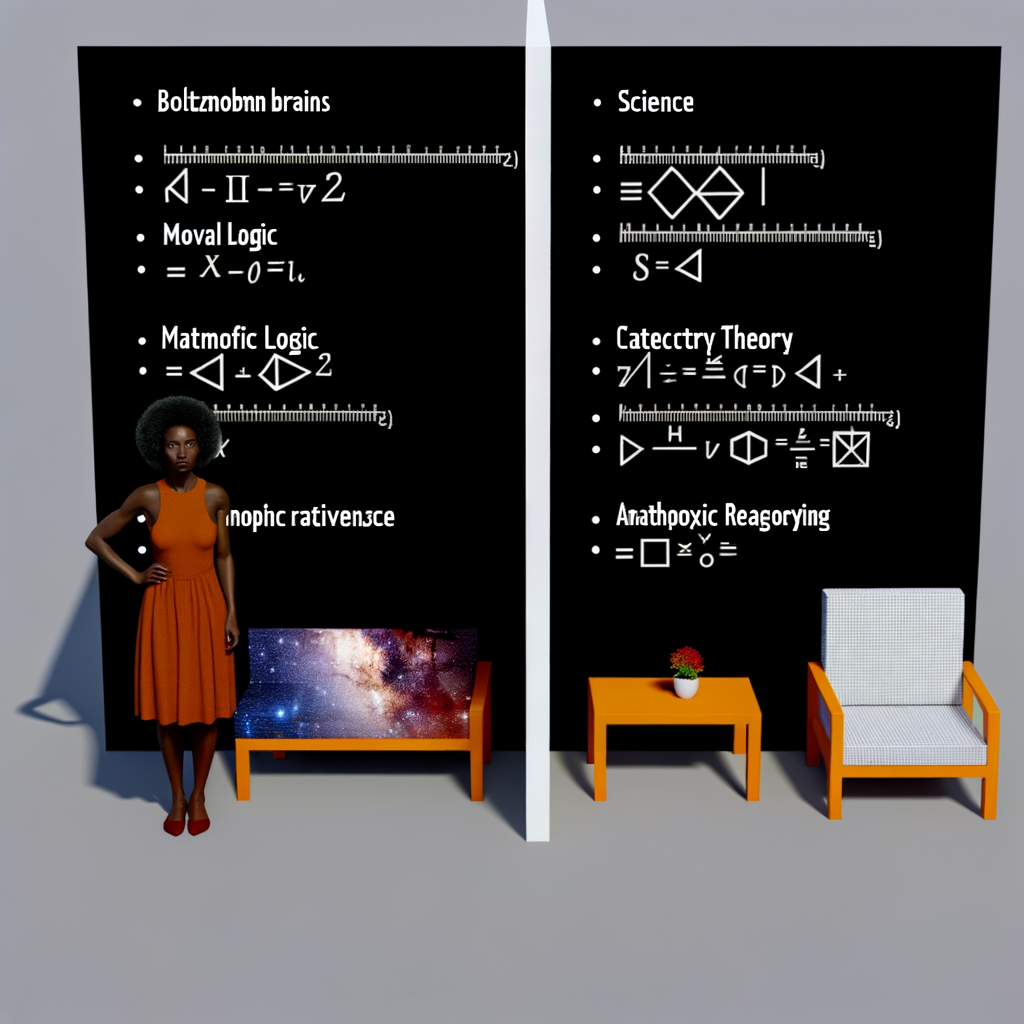

If you like unsettling thought experiments (Boltzmann brains, eternalist time, secret-hermetic backstories), you’re basically cruising the intersection. Pull up a chair. I’ll pour you something strong and explain why mathematicians and logicians show up unannounced at this party and never leave.

## The divorce that never actually happened

The nineteenth-century university institutionalized a split: natural philosophy became `science` with labs and grants; the abstract work stayed labelled `philosophy`. But science doesn’t float on empirical air alone — it rests on philosophical bedrock: that there’s an external world, that measurements mean something, and that repeated experiments are informative.

Those are not empirical axioms; they’re philosophical theses. Once you notice that, you start seeing the joint bank account: logic, probability, and mathematics are the account managers.

## Where the weird stuff comes from (and why we should care)

Early-modern natural philosophers often dabbled in alchemy and hermeticism. You can trace the experimental method and laboratory technique back to those practical pursuits. The mystical impulse got domesticated into apparatus, but the hunger to decode patterns that aren’t immediately visible stayed. Today the hunger appears as very dry, very technical arguments in measure theory and model theory—still decoding patterns, just with nicer notation.

Why does this esoterica matter? Because the universe sometimes forces you to be weird before you can be precise. Cosmology, the philosophy of mind, and foundations of probability are fields where sloppy metaphysics makes your math give embarrassing answers.

## Boltzmann brains: the party-crashers of cosmology

Here’s textbook awkwardness: in some eternal cosmologies, random fluctuations over infinite time will, with nonzero probability, assemble conscious brains that have all the memories you currently report. If such Boltzmann brains outnumber ordinary observers, then probabilistically you should expect to be one.

This is funny, but not just a joke. It diagnoses a kind of cognitive instability: a theory that predicts that observers will typically be hallucinations undermines our warrant for the theory itself. Math is the villain and the savior here. Which mathematical tools get pressed into service?

– Measure theory: How you define a measure over infinite spacetimes matters. Sigma-finiteness, regularity, and choices of cutoff can flip whether Boltzmann brains dominate. The devil is an uncountable detail.

– Probability & ergodic theory: Typicality arguments depend on limiting frequencies. But when your sample space is something like “all observer-moments in a forever-unfolding universe,” typicality ceases to behave like common sense.

– Algorithmic probability & Solomonoff induction: Some philosophers suggest using algorithmic notions of simplicity to prefer cosmologies that don’t predict rampant random-observer creation.

If you’re a cosmologist or a philosopher, you must choose bookkeeping rules. If you pick them without justification, your theory will be a pretty story that collapses on contact with Bayes’ theorem.

## Time: loaf, slice, or toast?

Eternalism (the block universe) says every moment exists equally. Presentism says only the present is real. Temporal logic, modal logic, and the math of dynamical systems all sneak into these debates.

– Modal logic & temporal logic: Tools like linear temporal logic (LTL) and branching time logics let us talk precisely about “always,” “sometimes,” and “next.” They’re indispensable when your metaphysics tries to be crisp about becoming.

– Category theory & topos theory: Sounds fancy and it is—because these frameworks unify geometry, logic, and computation. Topos-theoretic approaches give you models where time and truth-values behave in non-classical ways, letting philosophers test intuitions about becoming and persistence.

– Computability & complexity: If a conscious process is computational, questions about free will and predictability shift into questions about computability and resource-bounded reasoning.

So the tactful answer to “why does now feel like anything?” mixes entropy gradients, causal structure, memory, and mathematical models of information flow. The ontological picture must be married to a rigorous account of agent-relative indexing — the kind of math philosophers historically outsourced but now aggressively hoard.

## Logic, set theory, and the weird corners where answers live

Foundations of math give the tools to formalize metaphysical claims. Some cross-sections worth noting:

– Model theory: When you ask whether a theory describes a world or just a structure, model theory tells you how different models can realize the same axioms and why “obvious” metaphysical commitments are often artifacts of the chosen language.

– Set theory & independence: The Continuum Hypothesis taught us humility. Many metaphysical questions map to set-theoretic independence results—meaning there isn’t a unique crisp answer without extra principles.

– Non-classical logics: Paraconsistent logics let you live with contradictions (handy for inconsistent but useful scientific theories). Modal logics let you quantify over possibilities. Intuitionistic logics force you to be constructive — dear to the heart of some philosophers of mathematics.

These are not academic navel-gazing exercises. They change what counts as a legitimate explanation and how we model observers, agency, and evidence.

## How to talk like a responsible academic weirdo

If you want to turn this cocktail of weirdness into a research project (or a sane thesis), be pragmatic:

– Pin down one crisp problem (e.g., “Can we define a gauge-invariant measure on inflationary spacetimes that avoids Boltzmann dominance?”).

– Use the right math: don’t wave your hands about infinity when measure theory or nonstandard analysis will do the heavy lifting.

– Acknowledge alternatives: show you know which kind of logic or probability theorist will disagree and why.

Admissions committees want rigor packaged with curiosity, not romantic epiphanies about cosmic meaning.

## Takeaway — the long and short of the house party

Science and philosophy never properly split; they rearranged their furniture. The weird stuff—esotericism’s legacy, Boltzmann brain paradoxes, block-universe discomfort—is the houseplant that survived the move. It looks odd, but it’s also where the best arguments hide.

We bring math and logic to sort the confusion because they keep the receipts: measures that behave, logics that model possibility and time, set theory that reveals when our questions are underdetermined. Sometimes the math tells us to toss a cosmology; sometimes it tells us to reassess how we count observers; sometimes it embarrasses an otherwise pretty story.

I like to imagine the departments as roommates who still share shampoo: the door says “Science,” the mug says “Philosophy,” and the shampoo bottle is labeled “Mathematics & Logic.” Nobody’s moving out.

So here’s the question I want to leave you with (and yes, it’s meant to ruin your weekend): if your best physical theory implies that most observers are transient, randomly-fluctuated brains whose memories are false, what, precisely, are you still allowed to believe about that theory?